Mariah Long

Mariah was previously the Program Manager of End Slavery Now. She graduated from the University of Cincinnati's DAAP program with a degree in Digital Design.

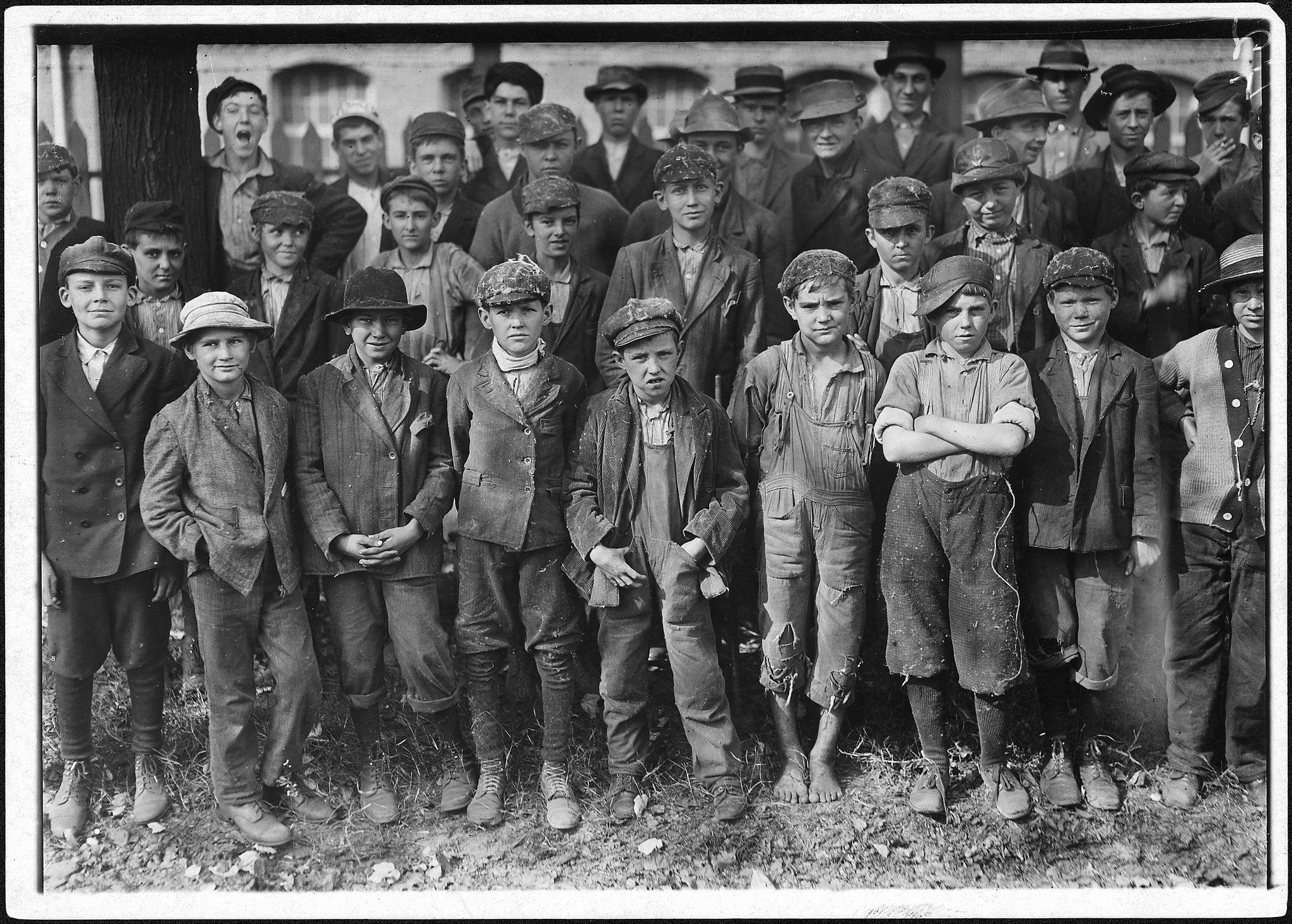

Child labor has made its way back into the news lately as we start to more strictly evaluate where and how our goods are produced. In the instance of child labor, there are exceptions that we as a western society have accepted as well as violations that prompt swift action. Violations may result in the closing of a factory or financial penalties. However, when looking at these exceptions and violations, the line can get blurry when it comes to determining which cases are, in fact, illegal.

Anyone under the age of 18 is considered a minor, or a child, in the United States. But, a child age 14 or above is legally allowed to work; in fact, many teenagers get their first jobs at restaurants or other local establishments, and no one calls for a boycott because these companies use child labor. There are regulations involved, but the employment of a minor can be legal.

In contrast, here are instances of child labor the United States Department of Labor deems illegal:

Across the globe, there are countless stories of extreme forms of child labor in industries like fishing, carpet weaving, agriculture and construction. Some industries have a history of abusing child laborers to make specific types of products. These abuses of child labor are terrible and should not be condoned, but unfortunately, not all cases are black and white. Ideally, all children should have the option to go to school and get an education instead of working away their childhood. But what happens when education is not an option, the work circumstances are not abusive and child labor is deemed necessary for the survival of the family?

As with most human rights abuses in the world today, we want a quick fix. This has led many to campaign for a ban on all forms of child labor (regardless of whether it is abusive or not) in all levels of supply chains. The fact is, some children grow up in situations where they have to work to help support their family. The question of “should this be allowed?” gets a little more complicated when you start to look into a variety of situations.

According to one of our partners that run a social enterprise, child labor laws have prevented skilled bead workers from teaching their children the trade until they are much older. As a result of those missed years of training, the quality of the product their community is producing has gone down and is worth less.

Most companies have some sort of anti-child labor policy that is typically enforced in a black and white manner. While policies against exploitation are crucial, some anti-child labor rules and regulations don’t address wider issues faced by the working community and may create bigger problems when enforced.

For one factory, strict anti-child labor laws caused it to shut down after a child was found in the premises. The child was not working, and he was only there because his mother could neither afford to have anyone look after him nor quit her job and stay at home with him. As a result of the factory closure, everyone in that town is now out of a job with no other way of finding employment.

Before anyone says something along the lines of “those young boys should be in school and not doing bead work” or “the factory should’ve been compliant with the laws,” the reality is that those are not feasible options for these communities. There are little to no social safety nets, and more importantly, they lack sustainable economic opportunities that would enable them to pull themselves out of these conditions.

These restrictions that result in child labor law violations are often ignored by developed societies, and it becomes easy to condemn these communities for their “backwards” practices. But let me challenge you with a more familiar scenario:

Children grow up on a farm, and at a young age, they start helping with the morning feeding and cleaning of the farm’s animals. They help their parents however they can around the farm to get the work done, and this work continues as they grow older.

This scene can be observed across thousands of fields across the United States. Are these kids working? Yes. Are they paid a wage? Probably not (unless you count an allowance). Are they learning a skill and helping their family business? Absolutely. However, I don’t know of many people protesting farmers for the labor their children are doing on their farms.

Seen as developing “grit” and a “solid work ethic,” this form of child labor is accepted, if not encouraged.

Child labor is a complicated topic when it comes to what is right or wrong, especially on a global level. As we urge businesses to look at their supply chains abroad and to ban child labor, it is critical that we also make the effort to understand the different challenges that families and workers abroad face. Unless we address the insecurities that resulted in child labor in the first place, these anti-child labor policies might end up creating new issues and could further impoverish these people. Additionally, we must take care not to separate ourselves – as a developed, western society – from the topic of child labor. After all, we criticize other cultures for conducting the same activities that we allow on our own land.

Ask your favorite companies to examine their supply chains

Pray, and hear testimonies about victories against modern-day slavery